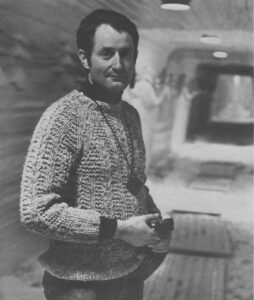

Peter Suschitzky, BSC, Director of Photography on THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, is the son of a famous cinematographer, Wolfgang Suschitzky, who came to England from Vienna, via Holland, in 1935 and who became closely connected with Paul Rotha of the British documentary film unit.

Born in Hampstead, London, Peter entered the British film industry in his late teens. Having been almost literally raised in the world of filmmaking, his progress was rapid and, by the age of 22, he was a fully recognized cinematographer.

An Ice Planet, a Bog

Planet and a Cloud City

presented photographic

challenges of a sort

seldom encountered

in our local galaxy

The son of a famed cinematographer, Peter Suschitzky, BSC, Director of Photography on THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, entered the British film industry in his teens and had become a full-fledged cameraman by the age of 22. Photographing two Ken Russell pictures (LISZTOMANIA, VALENTINO) prepared him for the wild goings-on he encountered in EMPIRE.

His first film as Director of Photography was IT HAPPENED HERE, a clever evocation of what Britain might have experienced if Hitler had won the war. In the 1960’s he photographed PRIVILEGE and CHARLEY BUBBLES. It was in association with director Ken Russell that he graduated to movies of international stature, photographing VALENTINO and LISZTOMANIA. His feature credits also include ALL CREATURES GREAT AND SMALL.

Like many top cinematographers working today, Suschitzky also photographs commercials between feature assignments. These have taken him to many countries (including the United States and Australia) and have won him several awards, including a Best Commercial award at Cannes. THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK is the first space fantasy he has photographed.

Upon the completion of his work on EMPIRE, he was interviewed in London by David Samuelson as follows:

DAVID SAMUELSON: It is my impression that you were “born” more into photography than into the film industry, per se; isn’t that the case?

PETER SUSCHITZKY: Whilst I was a child I had learned a lot about photography and my father certainly helped me, teaching me all the processes of printing and developing. I remember starting out with gold-toning daylight printing in those days. My first camera was a Kodak box camera, but I developed lots of other interests when I was growing up and it certainly wasn’t a foregone conclusion that I should go into films straight from school. However, I took various exams at the end of school and was almost on the brink of pursuing something to do with music when it occurred to me that I should really follow what I knew I could do rather well-namely, photography.

QUESTION: From that general interest in photography, how did you focus your emphasis toward cinematography?

SUSCHITZKY: I had always been interested in film work, but I thought I would go to film school in order to find out if that was the direction I really wanted to follow. I went to a film school in Paris called IDHEC. When I finished there, I got a job as a clapper-loader boy in a small studio in London. Very soon after that I managed to move on from that studio (which was only making commercials) to another part of the same company that was producing documentaries for TV. I spent six months there and at the end of that time I was asked by the head of the company if I would like to go to South America to be a cameraman on a series of documentaries. So there I was, after only maybe a year and a quarter in the industry-1 was 20 or 21, I think being asked to go and be a cameraman.

QUESTION: And how did it work out?

SUSCHITZKY: It was a one-man-band operation-just myself and a journalist and I spent a year in South America, hardly ever seeing rushes. I think I picked up an awful lot of experience in what it means to be in films, because I had to do sound recording, see my equipment through customs and book hotels, as well as do the lighting and the operating, the loading and everything that a one-man-band does. When I got back to England I was fortunate enough not to be obliged to work because I had saved up some money. At that time I had a call from an ex colleague of mine who was making a film on weekends in 35mm, and he asked me to photograph it. It turned out to be a film called IT HAPPENED HERE, directed by Kevin Brownlow. It was my first feature film and it subsequently had quite a wide public distribution. I think I was 22 at the time and it really was plunging in at the deep end, as my previous experience had not quite prepared me for a feature movie. But the results seemed to be alright, and I just learned by my mistakes.

QUESTION: What was your next step?

SUSCHITZKY: Well, I now had something to show-which is always the first stumbling block for any cameraman, director or actor-and that helped me eventually to obtain the assignment for my first professional feature two or three years later. I then photographed two features for Universal. One was Albert Finney’s CHARLIE BUBBLES and the other was a film with Peter Watkins called PRIVILEGE. That was a good period in British films, the mid-Sixties, when there was a lot of activity over here. I was really very fortunate and took advantage of my luck. Since then I have not, perhaps, photographed as many feature films as I could have, because I have never liked going straight from one film to another. Even so, I suppose I must have been involved in 20 features as a Lighting Cameraman. Going backwards, the most recent pictures have been THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, VALENTINO and LISZTOMANIA (with Ken Russell), another two films with Peter Watkin, three or four with Warris Hussein (including a film with Sandy Dennis called THE MILLSTONE), a film with John Boorman called LEO THE LAST (starring Marcello Mastroianni), two films with Claude Whetham (one of which is often called THAT WILL BE THE DAY), and a film with Peter Hall, MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM. I am probably leaving out quite a few as I go through, but those are the principal ones. Now I am nearly 40.

QUESTION: How did you get involved with THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK in the first place?

SUSCHITZKY: I was approached about photographing the original STAR WARS, so my contacts with George Lucas and Gary Kurtz date back a few years now. In any event, as I suppose everybody knows, I didn’t do the film; Gil Taylor did it. But then they approached me again about photographing THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK. This happened a good year-and-a-half before production began, which was certainly the longest term of involvement I have ever experienced. I was always impressed with the extent to which they planned and the way they thought everything out so very thoroughly. Over the course of that year-and-a-half, I had several meetings with them, either here or in Los Angeles. If /found myself over there, I would go up to San Francisco and visit their studio and talk with the people who were going to be doing the model work. I’d ask their advice and give them my opinions and feelings about what I would be doing, and we had a fairly useful exchange, I would say.

QUESTION: How special is working with special effects?

SUSCHITZKY: Well, before you actually experience it, the term can be slightly intimidating. Over the years, when I have heard terms which to me denoted something I had never done myself, it was sometimes just a reference to a field which I knew little about. But, in fact, there is no mystery to it. It is just one of those processes which one can under-stand-and certainly in lay terms-understand fairly rapidly. Having done it all now, I must say that I am not intimidated by any of the terms anymore. I’ve had a lot of matte work to be done on VistaVision, and I had never seen a VistaVision camera in my life. And before I had seen it, I certainly didn’t know what it was going to be like to work with. I can’t say that I am in love with it, but the results, after a lot of toil and tears, were worth the effort one put into it. Taking that camera to Norway-into the extreme cold-was not a very funny experience. It refused to get up to speed on several occasions. The film broke and we had all sorts of problems with it, but in the end, I’m sure that the results of the matte work being done on a large format are going to be worth all the extra trouble.

QUESTION: What did being involved with a production so long beforehand mean to you?

SUSCHITZKY: Being approached by George Lucas and Gary Kurtz a year-and-a-half before shooting began-even before they had settled on a director, in fact-didn’t mean a constant involvement. It meant meetings now and then over that period, with a greater intensifying effect toward the end of the period. It meant getting excited about a really interesting film-or trying not to get excited about it, in case it didn’t happen. I met Irvin Kershner, the director, about a year before we started shooting, I suppose, and we immediately struck up a good relationship. I feel that we have kept that up right throughout the production period-which, I must say, I feel very happy about. After about six months of shooting and a year-and-a-half of preparation, to come out the other side and feel that we are still friends is very pleasing. But to answer your question more specifically, it meant, toward the end of the period, visiting the studio, talking with the Art Director and looking at his plans, going away, thinking about them, coming back and throwing in ideas and asking them to do certain things. It meant the bending backwards and forwards of ideas and slowly having to plan how I would light the sets, because some of them were enormous.

QUESTION: Isn’t it true that they built a stage specifically for this film—a permanent stage?

SUSCHITZKY: Yes, although, obviously, it will be used for other films in the future. Some of the sets needed a lot of thought, as they involved great expense in terms of man-hours and equipment rigging. I suppose it is fair to say that I am a slightly “untechnical” cameraman-more instinctive than technical-but obviously every cameraman has to know roughly what he is going to need in the way of equipment, because there is no use saying: “Well, I might need 100 Brutes or I might need only 50 Brutes.” When it comes to those figures, a company is going to want to know if you really need 100, or 50 or if you can make do with two. So the really big sets needed a lot of thought. In fact, the small ones did too. Sometimes the small ones were more exciting to work on than the larger ones.

QUESTION: To what extent did you have to plan your work to accommodate special effects?

SUSCHITZKY: I have never been involved in a film with quite so many ef-fects-and half-finished sets which will look finished when the matte work is done at the end. All of that needed very careful planning, because it was quite obvious that my lighting of a part of the set (the rest of which was to be matted in) would commit the matte artist to a certain way of painting his matte, and it required an act of imagination to try to picture in my mind what the thing was going to look like when he finished. In regard to that and the many other complex technical problems inherent in this production, I just want to mention that I was immediately impressed with the seriousness with which George Lucas and Gary Kurtz approached the proj-ect-to the point where I have to say that I’ve never worked with producers who had such thorough technical knowledge of the medium. They were very keen that we should get the best possible result on the screen. They said, “What do you want to test? Which cameras do you want to test?” So I had total freedom to bring in any anamorphic system I wanted-not that the choice is great. I was even approached by one man in this country who was trying to persuade me to use a three-dimensional system, but when I asked him whether it had been used before, he said that it had only been tested in Moscow. I thought it best to put that out of mind for a few years.

QUESTION: When you were doing comparative tests you chose to do your special effects photography in VistaVision. Why was this—and why VistaVision in preference to 65mm?

SUSCHITZKY: I can only answer that by saying that it wasn’t my decision. That had already been made. They had, I believe, used the VistaVision system on STAR WARS.

QUESTION: Did you use VistaVision only for plates or did you use it for anything else?

SUSCHITZKY: The VistaVision camera was indeed used for plates-but it was also used for live action material which would later on be combined with plates-so there was quite a lot of shooting in the studio with the VistaVision camera and the actors in front of a blue screen.

QUESTION: What photographic equipment did you use for the rest of the filming?

SUSCHITZKY: On the rest of the picture we used a combination of the PSR and Panaflex-X cameras. Toward the end of the filming-for the last two or three months-we switched over to a normal Panaflex. We then used the Panaflex-X as a second camera and an Arriflex as a third camera. Because there were many difficult and physically awkward sets, which involved climbing over various forms and up ramps and so on, we needed a lightweight camera, / operated the second camera a lot of the time, as I quite enjoy picking off things whilst the main camera is working. We had a full range of lenses from 30mm upwards, but as far as I can remember, we never used a zoom.

QUESTION: When you were working with the VistaVision camera, did the fact that the lens focal length of this equipment has to be twice that of normal anamorphic give you a depth of field problem?

SUSCHITZKY: It did really, because we had a lot of scenes which involved a pilot in a spacecraft against a blue screen. In order to get a good matte line, one would have to hold not only the pilot and the foreground sharp, but also the distant wings and tail, which meant working up to f/12.5 or f/16 on occasion.

QUESTION: To what extent was a second unit involved in the filming of THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK?

SUSCHITZKY: We had two units working on the film continuously. I had a second unit which was designed to work alongside the main unit and pick up little bits and pieces that were left behind. It then developed into a unit to pick up quite big chunks which we had to leave behind, and also the matte work. I coped with the two units on different stages for the first 12 weeks of the picture, with the aid of a bicycle which I used to commute, and carrying a radio to call me back to the main stage. I then decided, after 12 weeks, that I needed another cameraman to help me out with the second unit and the matte work. I got Chris Menges (and for a short period I had to have somebody else when he had to go away for a bit), but the cooperation was always very satisfactory. I must say that he matched what I wanted perfectly and never resented the fact that I would cycle onto the stage with no notice at all and ask him to change things. But it meant that I was stretched on the film and I used to have people ribbing me about my bicycle, which must have done quite a few hundred miles between the stages and the different units.

QUESTION: You said earlier on that you hadn’t had a great deal of experience with special effects. What differences did you have to make in your shooting techniques in order to accommodate special effects on this picture?

SUSCHITZKY: When you use the term “special effects”, the only thing I was relatively unfamiliar with was matte work, although I had done some, and I now feel quite confident about it. That mystical term, “special effects”, didn’t involve anything else that I hadn’t experience before, and I don’t think I had to alter my lighting technique at all, apart from the fact that occasionally we needed a very high light level in order to cope with the depth of field required for the matte shots. The other special effects were the normal sort of things, such as explosions and practical lights in machinery and my lighting was governed by that sort of thing on a technical level. Whenever we had the character R2-D2 on the set, which was very frequently, I had a special problem. I had to discover early on what was the right light level for him, so that he would look good photographically, yet his practical lights would shine through, but I don’t think this is a very unusual or particularly interesting technical point, and I don’t think I had to change my lighting style at all because of any special effects.

QUESTION: How do you define your normal lighting techniques?

SUSCHITZKY: Well, I like to think that I change the lighting according to the demands of a scene and the set. In my work the lighting generally always evolves out of how the scene is played and how the set looks. Thus, I am never 100 percent sure ofwhatlam going to do before we shoot. Naturally, I have to know approximately what I am going to do, because I have to plan what’s going to be rigged. I think that when you see THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK you will see that there are scenes which have hard light and are extremely contrasty, stretching the limits of the emulsion, and some have soft light. Some are lit from underneath, some from overhead, and some from behind. I hope that this apparent disparity of styles will actually bring its own sort of unity to the film and won’t create a fractured effect. I actually feel that there is an internal unity to the lighting style, but there wasn’t one imposed from the outside that said that we were going to light everything from the right or from the left, or that it all had to be soft light or hard, all on a wide-angle or a telephoto. The style varies from sequence to sequence, but I really think that it has its own unity.

QUESTION: Were there any lighting set-ups of a particularly unique character?

SUSCHITZKY: There were some very tricky set-ups indeed. We had one set with a glass tube in the middle of it, with Luke Skywalker suspended in a kind of liquid. I don’t know whether the scene survives in its entirety in the finished film, but I had to devise a method of lighting this tube so that it would be very bright and the rest of the scene would be extremely low key-the tube would be the main source of light in the set-and I hit upon the idea of suspending a large mirror halfway up the studio above the set and a searchlight down below. The light from the searchlight would bounce off the mirror, which worked marvelously well until the mirror shattered once or twice, I believe, from the heat of the searchlight. There were other sets which presented their own difficulties.

QUESTION: What were some of your other challenges?

SUSCHITZKY: There was another set in which a sword fight was to take place between two of the characters. When I looked at that set it struck me as being rather like a model for a stage set. In other words, it looked unfinished. It certainly had no walls at all; it was a series of ramps and discs and blackness. I was extremely concerned about that set and I thought about it a lot, about how I was going to make it work and look believable and look dramatic. Then I decided to light the whole thing from underneath, as the floors had been made translucent. In the black areas I placed Brutes and had shafts of light penetrating the darkness. Then the whole set was filled with steam, which made it photographically very impressive, but physically very uncomfortable, since it was like working in a Turkish bath. We were quite high up in the stage and we all suffered for quite a number of weeks, but it was one of those sets which made me feel uneasy before I entered into the shooting of it because it looked so unreal, so unworldly and unlike anything I had ever done before. I was concerned about it looking dull, in fact, because although there seemed to be plenty of material in the set, it was all either on the floor or on the ceiling. The fact is that unless one goes for extreme angles (and you usually can’t do that right through a long sequence), the camera is pointing straight ahead and not up or down. There was nothing for the eye to look at straight ahead except blackness, because all the set elements were on the floor or the ceiling. I was concerned about the scene looking interesting and about the eye having something to look at-but, in the end, I think we succeeded in overcoming those problems-all of us working together.

QUESTION: You said you used steam as one of the means of diffusion. Did you use smoke at all?

SUSCHITZKY: The steam in this particular set was there because it suited the scene that was being played. I used very little smoke, except occasionally when the scene actually called for it because of explosions. I used to use smoke quite a lot a number of years ago, but I have always been a non-smoker and I’ve gotten more and more around to the idea that breathing in smoke all day and going home smelling of smoke is far from a pleasant experience and probably not worth it in the long run. It may be better to have a cleaner image and better health. (This doesn’t mean to imply, however, that I haven’t admired the results that other cameramen have got with smoke. In fact, I have enjoyed what I got by using smoke.)

QUESTION: Was there any one set that was especially awkward to work in?

SUSCHITZKY: We did have one set which is probably the most awkward set I have worked in for many, many years. There were plenty of difficult sets, but this one was really physically awkward. It was the house belonging to the Wampa creature, played by a Muppet, and as he was quite small, they built the house to suit him and not to suit a human being. Then we had to place Luke Skywalker (a human being) in the set and he could only sit down in it. Even so, he just barely escaped knocking his head against the ceiling. The set had three sides and virtually nowhere to conceal the lights. It had a fire going and that’s about all. I found it very difficult and painful to light and I had to crawl on my hands and knees into it, as one would in a mine at the coal face.

QUESTION: Did the robots present any special lighting problems — reflections from their metallic surfaces, for example?

SUSCHITZKY: The mechanical characters in the film didn’t present any special problems, apart from C-3PO, who was very shiny, thus causing one to be very careful about reflections-seeing oneself with equipment reflected in his surface, to be specific. There were people inside both of the robots. C-3PO, in fact, has an actor inside of him all the time and that gives him a very particular character. I think the actor is very clever at it. R2-D2 was portrayed by a series of different models, sometimes radio controlled, sometimes pulled along, and sometimes with a small man inside him, according to the demands of the scene. Some of the models will roll on certain surfaces and do special things, and others will perform different functions. They don’t seem to be able to put allot the functions into one model.

QUESTION: Are there any other particularly unusual lighting set-ups that you can recall?

SUSCHITZKY: I can recall many, but they would not be too unusual. However, I can recall one instance when we were filming inside what we called “Cloud City”. I think it comes toward the end of the film, and it was basically a series of corridors and one long hall. Although we had quite a few corridors, one often wants to make a set look bigger than it really is. For example, in one particular shot-where the camera tracked down a corridor, around a corner, up another corridor, and then back into the same corridor-1 wanted to make the return into the same corridor look like a different one. So whilst the camera was round the corner, I worked out a series of light changes to be done rapidly during the shot, so that by the time we got back into our old territory, it looked like a new and differently lit corridor. I think the film was full of demands upon the mind like that, which amused me tremendously and made the whole thing much more interesting than it normally would be.

QUESTION: Most cameramen have their own little secret tricks or techniques and tend to guard them rather jealously. Do you have any of those?

SUSCHITZKY: No, I’m not a cameraman who has secrets. There aren’t any secrets, really. There are few technical tricks of significance. I don’t go into a film saying that I’m going to do the whole thing with a wide-angle lens or a #5 diffuser, because I think that is inflexible. I really feel that a cameraman should serve the film, serve the director, and not feel that he is going to superimpose his style upon every film, because the photographic style should ideally change from film to film, evolving from the dramatic demands of each particular film. I hope that I don’t sound pretentious when I say that, in terms of my own career, it may be the experiences outside films that affect me more than anything else-far more than other films, for instance. Hence, it’s probably the paintings seen, the music heard and the book read which may influence my work more than anything else. Now I don’t think to myself that I am going to manage a scene or film like a Mondrian or a Rembrandt, but I believe that if you are functioning well as a human being, that later on (maybe years after the event), you may subconsciously draw upon a personal experience that may have nothing to do with films-a piece of music heard, a book read, or somebody you met, and you just never know how it is going to come out. If you go into a film saying, “I’m going to do it all with a 50mm lens or a #5 fog”-you are locking yourself down and preventing yourself from being flexible. On the other hand, if you go into a film with a degree of uncertainty and an open mind-and you are secure enough to be a little insecure-1 think that you will emerge with a far more interesting result than if you go into it knowing precisely what you are going to do.

QUESTION: In summing up, do you have any final observations regarding your assignment on THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK?

SUSCHITZKY: Only that I haven’t enjoyed myself so much on a film fora very long time. I worked with a director with whom I really got along tremendously, who encouraged me to do my utmost, and so I had a ball on it really, and lots of large toys to play with. What more could one want? ■